Members of Family Frontiers hold up placards demanding equal citizenship rights for Malaysians outside the Kuala Lumpur High Court September 13, 2021. — Picture courtesy of Family Frontiers

KUALA LUMPUR, Oct 20 — The High Court had on September 9 made a historic decision to recognise that Malaysian women should have the same right as Malaysian men, under the Federal Constitution, to pass on citizenship automatically to their children born overseas.

So why did the judge make this decision? And what does it mean for children born abroad to Malaysian women who are married to non-Malaysian men?

Here’s a summary by Malay Mail, based on the High Court’s written judgment and other court documents:

What led to the court case: Automatic right vs application

For decades now, Malaysian women married to foreigners have found that their children born overseas are not automatically allowed to become Malaysian citizens, due to provisions in the Federal Constitution.

By comparison, Malaysian men who are married to foreigners whose children are born abroad automatically become Malaysian citizens, once the child’s birth is registered with a Malaysian consulate or the Malaysian government within the required period.

Malaysian women who would like their overseas-born children to have the same nationality as them, have to apply under Article 15(2) of the Federal Constitution.

Under Article 15(2), the Malaysian government “may” register anyone aged below 21 as a Malaysian citizen, if this person has at least one parent who is Malaysian and if this person’s parent or guardian had applied for the citizenship registration.

While it sounds simple, the pathway for these Malaysian mothers’ overseas-born children to be recognised as Malaysians actually tends to be a difficult one that could take years and years of waiting and trying, and with no guarantee of success.

Family Frontiers president Suriani Kempe had in court documents said that the Article 15(2) application process — which is the only option such Malaysian mothers can resort to — is “discretionary, tedious, takes an inordinately prolonged period for processing and the application is often rejected.”

This led to six affected Malaysian mothers together with Family Frontiers filing a lawsuit through an originating summons on December 18, 2020 in the High Court in Kuala Lumpur against the Malaysian government.

Members of Family Frontiers hold up placards demanding equal citizenship rights for Malaysians at the Kuala Lumpur High Court April 27, 2021. — Picture by Hari Anggara

The six mothers are Myra Eliza Mohd Danil, Adlyn Adam Teoh, a mother who wishes to be identified only as Devi, Choong Wai Li, Ng Mei Mei and Rekha Sen Mei-Mei.

All six had first tried to apply for their children to be registered as citizens under Article 15(2), but these applications were rejected — with no reasons given.

By the time they finally filed this court case, some of them had been waiting for more than four years without any reply from the government (and still none to this day) on their latest attempts.

The earliest time these mothers had made the first citizenship application for their children was in 2011 or even 2013, which means the journey for some of them had started 10 years ago.

Meanwhile, the clock keeps ticking, as the Article 15(2) pathway has an age limit of 21 years. In the process of waiting, some of the six mothers’ children are already in their early teens or having reached half of the age limit. Some may also have siblings who are Malaysian, just because they were born in Malaysia.

Here’s a chart showing how lengthy the process can be, based on the six mothers’ experience listed in court documents sighted by Malay Mail:

What happened before the case could be heard

The Malaysian government in January 2021 applied to have the entire court case struck out without being heard, but the High Court on May 6, 2021 rejected the government’s striking out application.

The High Court judge Datuk Akhtar Tahir instead decided that the lawsuit should be heard on its merits and held that it was not a frivolous case. The judge also allowed the home minister and the National Registration Department’s director-general to be added as defendants.

The judge had said the Malaysian government must give reasons to justify the apparent discrimination or distinction in the Federal Constitution’s provisions, namely where it states a child born in Malaysia can automatically be a Malaysian if either parent is Malaysian, while mentioning that a child born outside of Malaysia can automatically be a Malaysia if the “father” is Malaysian.

The Malaysian government failed in its second attempt to have the case struck out when the Court of Appeal dismissed its appeal on August 20, and the High Court on August 24 then proceeded to hear the mothers’ lawsuit in full on its actual merits.

Members of Family Frontiers hold up placards demanding equal citizenship rights for Malaysians at the Kuala Lumpur High Court April 27, 2021. — Picture by Hari Anggara

What the judge decided

On September 9, High Court judge Akhtar delivered his landmark judgment which held that Malaysia’s citizenship laws in the Federal Constitution should not be interpreted in a way that discriminates against Malaysian women.

But before looking at the judgment, let’s have a quick look at the laws that are the focus of this lawsuit:

Under the Federal Constitution’s Article 14(1)(b), every person who fulfills the conditions in the Federal Constitution’s Second Schedule’s Part II “are citizens by operation of law.” This means they are entitled or have the right to be Malaysian citizens because of the law, and do not have to apply for citizenship.

In this case, the Malaysian mothers are saying that two of the conditions in Part II of the Second Schedule — Section 1(b) and Section 1(c) — currently discriminate against women, as these provisions now only mention Malaysian fathers as being able to pass on their citizenship to their children who are born overseas.

Section 1(b) provides for every person born outside Malaysia to be a citizen automatically if their “father” is a Malaysian citizen at the time of the person’s birth.

Section 1(c) is similarly worded with specific mention of the requirement for the “father” to be a Malaysian citizen at the time of the person’s birth, but with the added condition that the person’s birth abroad is registered at a Malaysian consulate (or with the federal government if born in Brunei) within one year of birth or within any longer period that the Malaysian government may allow.

The six Malaysian mothers and Family Frontiers had asked for six court orders, including declarations that these two citizenship provisions were discriminatory and violates the Federal Constitution’s Article 8 (which protects Malaysians from gender discrimination), and a declaration that the two provisions should be read harmoniously with Article 8 for the word “father” to also include the “mother” of children born overseas.

One of the court orders that the Malaysian mothers had asked for was for the Malaysian government to issue citizenship documents to children born overseas to Malaysian mothers.

Judge recognises Malaysian mothers and their children’s hardships

Here’s a summary of the judge’s 24-page full written judgment dated September 27:

High Court judge Akhtar recognised how the same family could have both non-Malaysian and Malaysian children because of the government’s rejection of citizenship applications to the child born overseas, which caused the child born abroad to face mental suffering, being deprived of privileges for education, healthcare and travel and with further difficulties due to Covid-19 pandemic travel restrictions.

The judge noted for example that one of the six Malaysian mothers is separated from her foreigner husband and fears losing custody of her child to the husband, while another of these six mothers had been constantly detained and questioned by immigration authorities due to the different nationalities between herself as a Malaysian and her children whom Malaysia does not recognise as citizens.

The High Court narrowed down the case to three main issues, namely whether the Malaysian mothers had locus or legal standing to be able to bring the lawsuit to court, whether the High Court could decide on the issues in this lawsuit and whether these issues could be decided by the courts in the first place, and the proper application of the Constitutional provisions.

1. ‘Locus’ — the right to file the lawsuit

The judge noted that the government had argued that the Malaysian mothers cannot make a claim to citizenship for their children as Malaysian citizenship is a privilege rather than a right.

But the judge said that the government’s argument does not address the issue of discrimination, noting that citizenship “must be offered without discrimination” even if the granting of citizenship is a privilege.

The government had also argued that the six Malaysian mothers did not have legal standing as they could allegedly only file the lawsuit on behalf of their children instead of for the mothers themselves, as those who are aggrieved were allegedly the children and not the mothers.

But the judge said the mothers themselves had in court affidavits spoken of their grievances such as having to spend more on education and healthcare for their children due to citizenship not being granted to them, and that the government had essentially accepted the mothers’ grievances to be “real and not mere conjecture” as it had not disputed or challenged what they said.

“So it is illogical to argue that only the children are aggrieved, not the mothers,” the judge said.

The judge also dismissed the government’s third argument where it had claimed that the Malaysian mothers are abusing the process of law by coming to the courts only after their children’s citizenship applications had been rejected.

Brushing away this argument by the government, the judge pointed out that Malaysian mothers had to resort to court after their children were denied citizenship, saying: “There is no abuse and in fact filing this originating summons is the proper and legal procedure.”

Ultimately, the judge said the Malaysian mothers had the locus or the right to file this lawsuit in court, noting that these mothers’ undisputed grievances are “real and not imaginary” and that they have a direct interest in the decision of the issues in the lawsuit.

Merdeka babies sleep in their cribs in Hospital Kuala Lumpur August 31, 2018. — Picture by Razak Ghazali

2. Does the court have the power to hear this citizenship lawsuit?

The Malaysian government had argued that the court has no jurisdiction or power to decide on citizenship matters, asserting that the granting of citizenship is a policy matter solely for the government to decide.

The government had also argued that certain provisions in the Federal Constitution — such as Section 2 of the Second Schedule which states the government’s decision of citizenship matters “shall not be subject to appeal or review in any court” — expressly ousts or removes the courts’ powers to decide on citizenship issues.

The judge, however, said that such an ouster clause only applies to situations where the home minister has the discretionary power to grant or reject citizenship applications such as under Article 15, and that in those situations the minister’s exercise of discretion would not be subject to the court’s review.

The judge indicated that the court would still have the power to decide on citizenship matters when it involves Article 14, where Malaysian citizenship is given as a right or by operation of law, and is not given at the home minister’s discretion.

The judge also said it was “ironical” that the government was seeking to remove the courts’ jurisdiction in deciding this lawsuit by using the concept of separation of powers, pointing out that the ousting of the courts’ jurisdiction in this case would achieve the opposite and concentrate the powers of making, executing and judging on laws in the hands of one single branch of the government — the executive.

The judge had highlighted that the courts are empowered to interpret and apply the law in a way that will uphold justice and uphold the spirit of the Federal Constitution, which is Malaysia’s supreme law.

“In summing up on this issue, the court reiterates that it is not seeking to change the federal government’s policy of granting citizenship,” the judge said, pointing out that Parliament’s Hansard records show that the Malaysian government had long decided — during the tenure of the country’s second prime minister Tun Abdul Razak Hussein — to adopt the policy of granting citizenship to children born outside of Malaysia through the jus sanguinis principle (citizenship based on lineage or parents’ nationality).

“This court further reiterates that it is not seeking to change the policy or rewrite the law which has already been enacted by the federal government. What the court is endeavouring to do is applying the existing law and policy already in force in a manner which will find a remedy to the grievance of the Plaintiffs. The courts are surely empowered to do this,” the judge said.

Having already stated that there is apparent or obvious discrimination against the Malaysian mothers, the judge stressed that the mothers’ grievances are real and that the government “must not bury their head in the sand like an ostrich and state that there is no grievance or discrimination.”

3. Interpreting and applying the Constitutional provisions

The judge noted that the government had argued that the Constitutional provisions should be interpreted in a literal way, but said such an approach would downgrade the courts’ role to “rubber stamping” the provision without actually applying it in a “fair and just manner” and without considering the actual purpose of the provision’s enactment.

The judge said that all Federal Constitution provisions should instead be interpreted harmoniously and purposively to avoid any provisions from becoming pointless, adding that the citizenship provisions must reflect the Article 8(1) provision that provides for equality before the law.

As for the government’s arguments that the Constitutional provisions on citizenship are not discriminatory and do not violate Article 8, the judge disagreed.

The judge recognised that Article 8 does not give an absolute protection to Malaysians against discrimination on matters such as gender, as Article 8(2) — which starts with the phrase “Except as expressly authorised by the Constitution” — allows for discrimination in certain situations.

However, the judge said that the law must expressly state a situation as being an exception where gender discrimination would be allowed, and that such exceptions cannot be implied.

For example, the judge said that just because the Constitutional provisions on citizenship for those born outside of Malaysia use the word “father”, it did not mean that there is an implied exception to allow gender discrimination.

In order to expressly state an exception that would allow discrimination, the judge said a law should start with a phrase like “Notwithstanding Article 8.”

The judge further highlighted that Parliament’s Hansard records do not show a conscious effort to discriminate between mothers and fathers in granting citizenship to their children, and that Parliament’s debates were instead focused on whether citizenship should be given to children born outside of Malaysia and that the sentiment in Parliament was “to give citizenship based on loyalty, allegiance and attachment to the country.”

The judge also said that the government’s failure to provide any justification for the gender discrimination in the Constitutional provisions on citizenship meant that it can safely be assumed that there is no justification.

Children from Kampung Orang Asli Chadak, Ulu Kinta in Perak run with the Jalur Gemilang, September 15, 2021. — Picture by Farhan Najib

The government had argued that Malaysia’s accession or agreement to be bound by the international treaties Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) does not give the Malaysian mothers the legitimate expectation that the Malaysian government would interpret citizenship laws in line with such international obligations.

Among other things, the government had argued that this was because it had expressly made reservations or expressly stated that it would not follow CRC provisions on the right to acquire a nationality, and Cedaw provisions on equal rights of women with men when it comes to their children’s nationality.

However, the judge said legitimate expectation is not derived from international treaties, but said the Malaysian mothers’ legitimate expectation in this case is derived from their “natural instinct to give the best to the child.”

“It is only natural that a parent desires that everything of value be inherited by their children be it material or otherwise. In this case, the plaintiffs as mothers, value the Malaysian citizenship and are loyal to the country and this has motivated them to file this originating summons. Given a choice, these mothers would have avoided the courts at all cost.”

The judge pointed out that the Constitutional provisions that granted citizenship to those born outside of Malaysia were intended to “reward loyalty” as shown by the Malaysian mothers’ loyalty to Malaysia.

The judge also said the Federal Constitution should be interpreted to meet the needs of current time, suggesting that the way the citizenship provisions were worded could be due to historical reasons in the past.

“It could be the word father is used as at that point of time it was difficult to travel and usually it was the fathers who had to travel out of the Federation. Now anyone can travel easily,” the judge said.

Ultimately, the judge concluded that the word “father” in the Constitutional provisions — on citizenship for children born outside of Malaysia — must be interpreted to include the “mother” of children born outside of Malaysia.

The judge’s three orders in favour of Malaysian mothers

The High Court ultimately gave three brief declarations or court orders, including a declaration that the word “father” in the related Constitutional provisions includes the mother, and that therefore the children — of the six mothers and all other Malaysian women facing the similar situation — “are entitled to citizenship by operation of law” if all the necessary procedures are followed. These procedures would be similar to those that Malaysian fathers follow for their overseas-born children to be entitled to Malaysian citizenship.

The second order that the judge gave was for the government to extend the time for the mothers to comply with the necessary procedures, while the remaining order was that “all the authorities are directed to issue the relevant documentation” to give effect to the court’s declaration.

Family Frontiers president Suriani Kempe hands the #TarikBalikRayuan petition to Foreign Minister Datuk Saifuddin Abdullah outside the Parliament building in Kuala Lumpur September 23, 2021. — Picture by Yusof Mat Isa

What’s next in the courts

The Malaysian government, home minister and the NRD director-general had on September 13 filed an appeal at the Court of Appeal against the High Court decision.

These three had also on September 14 filed an application at the High Court to stay or temporarily suspend part of the High Court’s decision until the Court of Appeal decides on the appeal.

The part that they are seeking for a stay of is where the judge had ordered all the authorities to issue the relevant documentation such as identity cards and passports if citizenship is granted to the overseas-born children of Malaysian mothers.

The High Court will be hearing the stay application on November 15, while the actual appeal is scheduled for case management on November 10.

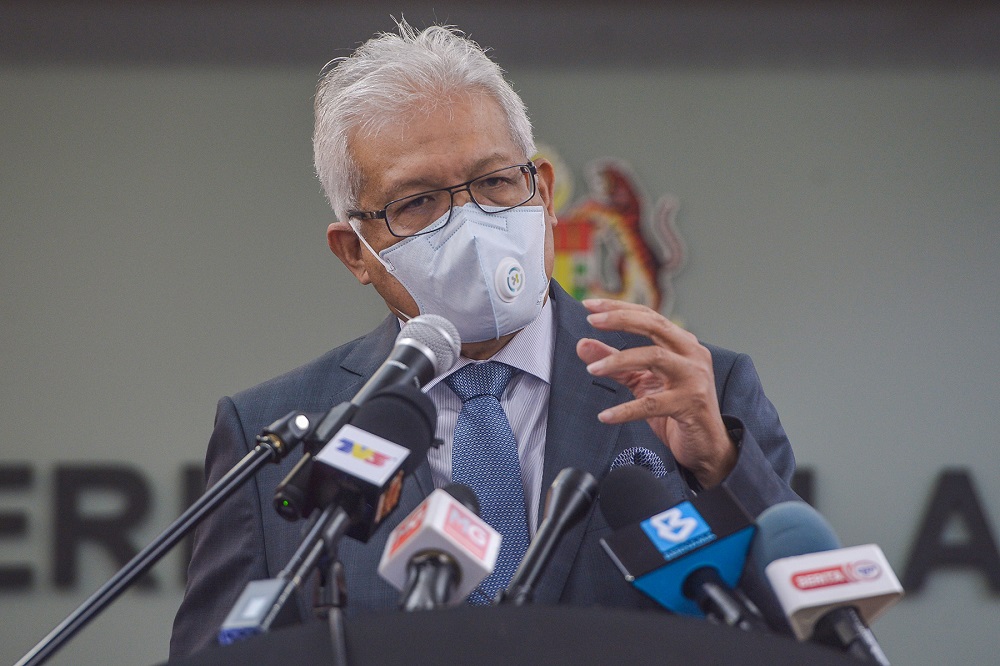

Home Minister Datuk Seri Hamzah Zainudin speaks during a press conference in Putrajaya September 1, 2021. – Picture by Miera Zulyana

How long more to wait?

After the government filed its appeal, Family Frontiers launched an online petition on Change.org to urge the Malaysian government to drop the appeal, arguing that justice is essentially being delayed and denied to the Malaysian mothers and their children.

Home Minister Datuk Seri Hamzah Zainudin had on September 22 told the Dewan Rakyat that his ministry had filed the appeal and also applied for a stay of the High Court decision, in order to prevent contempt of court and to not breach the Federal Constitution while the government pursues a proposed amendment of the Federal Constitution.

The minister said that the Home Ministry plans to seek for a new government policy to amend the Federal Constitution to make things easier for Malaysian mothers married to foreigners and who give birth overseas, while saying that such Constitutional amendment on citizenship matters requires consent from the Conference of Rulers in line with the Federal Constitution’s Article 159(5).

Hamzah on September 23 reiterated on Facebook that the rulers’ consent is needed before the government makes any resolutions to amend Constitutional provisions on citizenship, and on September 24 said the Cabinet had discussed the citizenship matter and had directed the attorney-general to raise it to the deputy Yang di-Pertuan Agong in the nearest time.

The Malaysian mothers had on September 23 delivered their petition to the government, and said the government should show its commitment to addressing their plight by immediately dropping the appeal and start implementing the High Court decision without further delay. At the time of writing, the online petition has garnered 32,606 signatures.

Family Frontiers on September 25 said the home minister’s reason for continuing to appeal the court’s decision was baffling, asking if the minister had sought commitment of MPs for a two-third majority support to amend the Federal Constitution and also highlighting the lack of timeframe given for the amendment with no remedy being given in the meantime.